Mother issues and the birth of an image

Anastasia Sosunova

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4]

[5]

Text

“No, madam,” I said to the woman in my ESL English. “That’s my mom. I came out of her asshole and I love her very much.”1

There is a quaint competition for the shortest story of all time. Among the most famous is a six-word story of unknown authorship: “For sale: baby shoes, never worn.” I contend, however, that the shortest story ever written has always been the single word: Mother. This is a story with a beginning, a conflict, and a myriad of possible endings. For some time now, I have been interested in the literature of motherhood, amassing my own tiny collection. This pursuit has intersected with another one of my obsessions: the printmaking plate, also known as a matrix. Originating from the Latin word māter (genitive mātris) meaning “womb,” “source, origin,” or “mother.” By the 1550s, matrix was used most commonly to refer to “a place or medium where something is developed,” like a mold in which something is cast, or a printmaking plate.

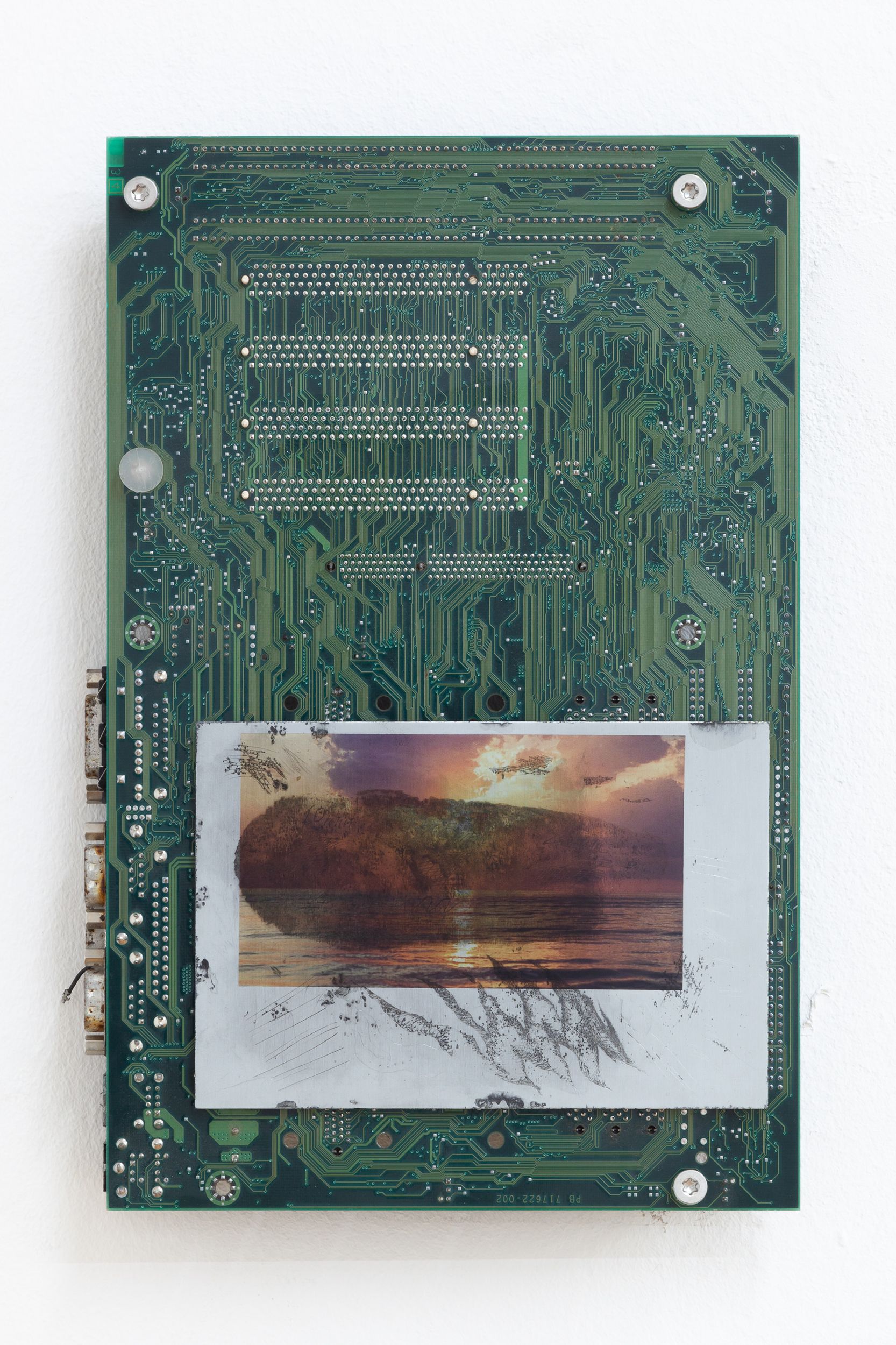

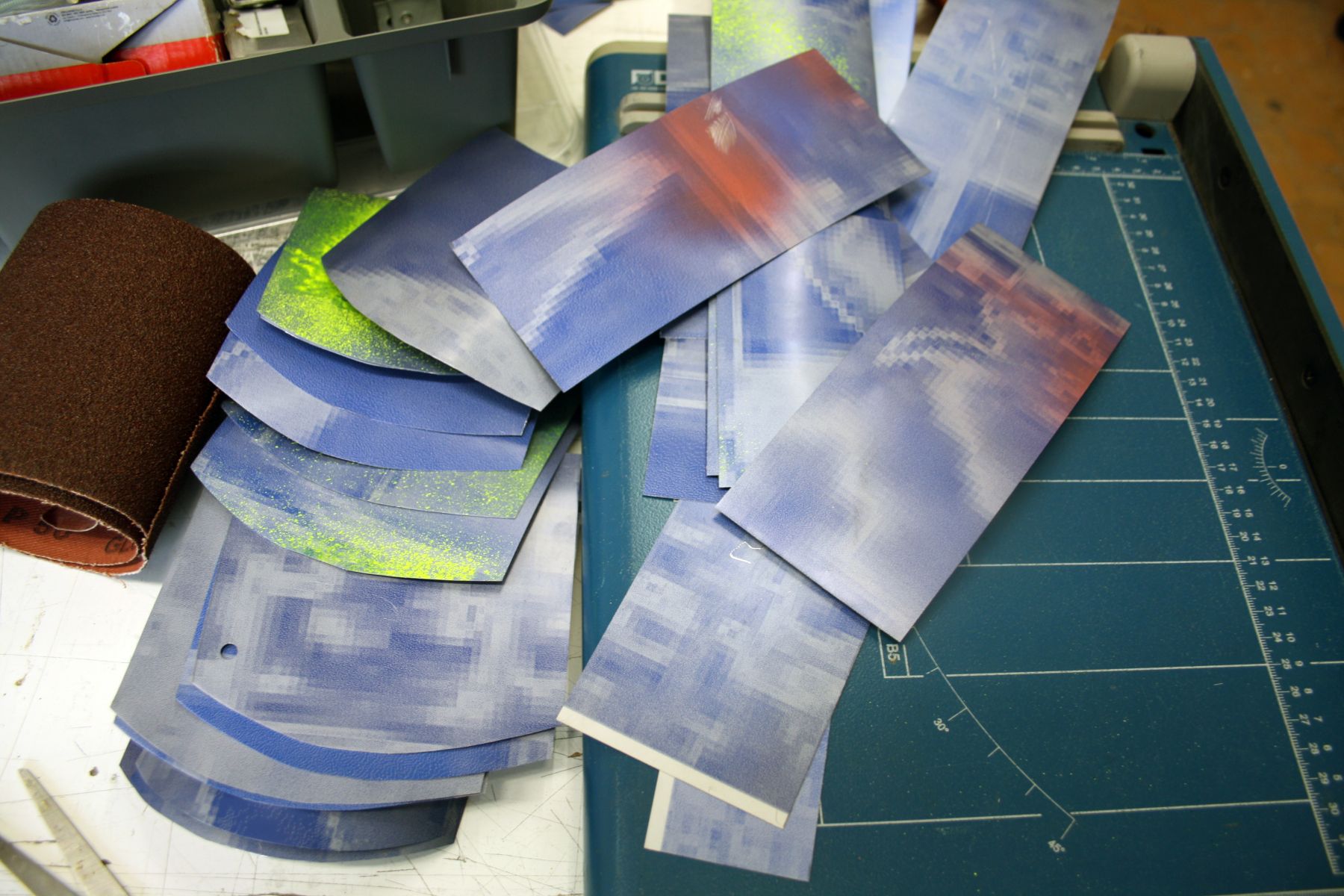

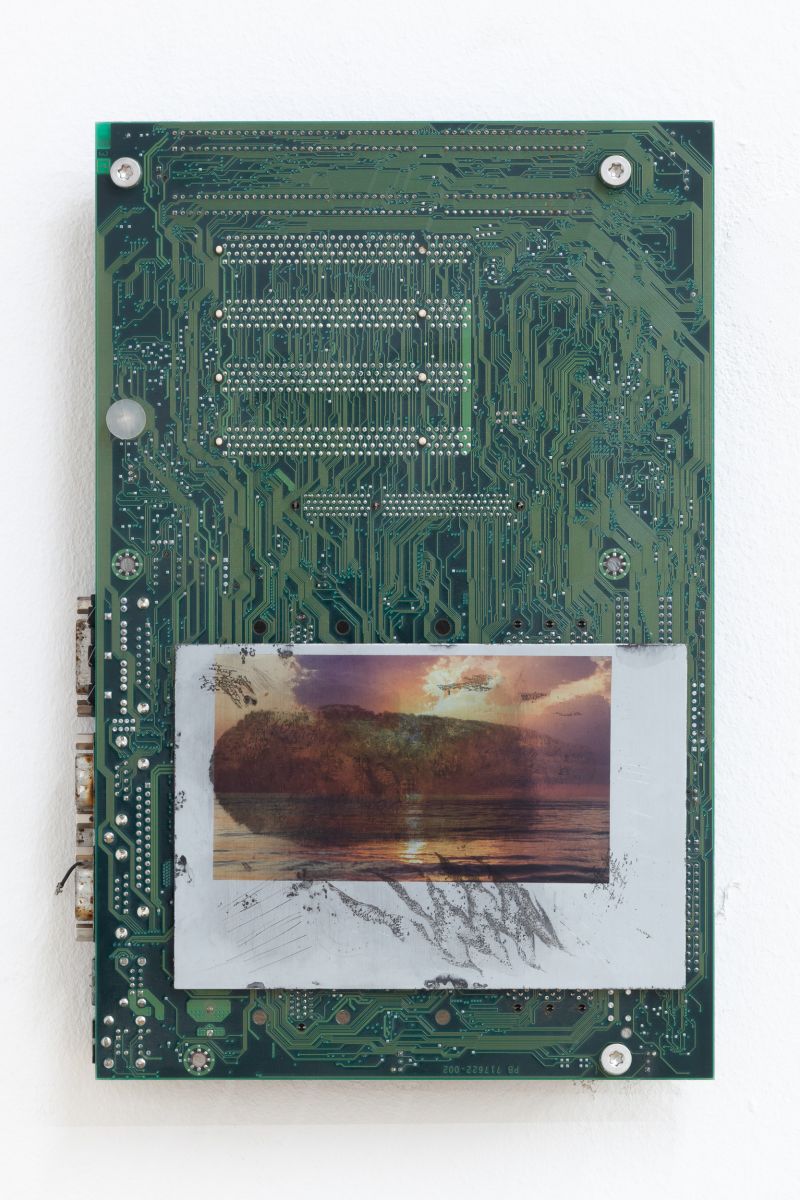

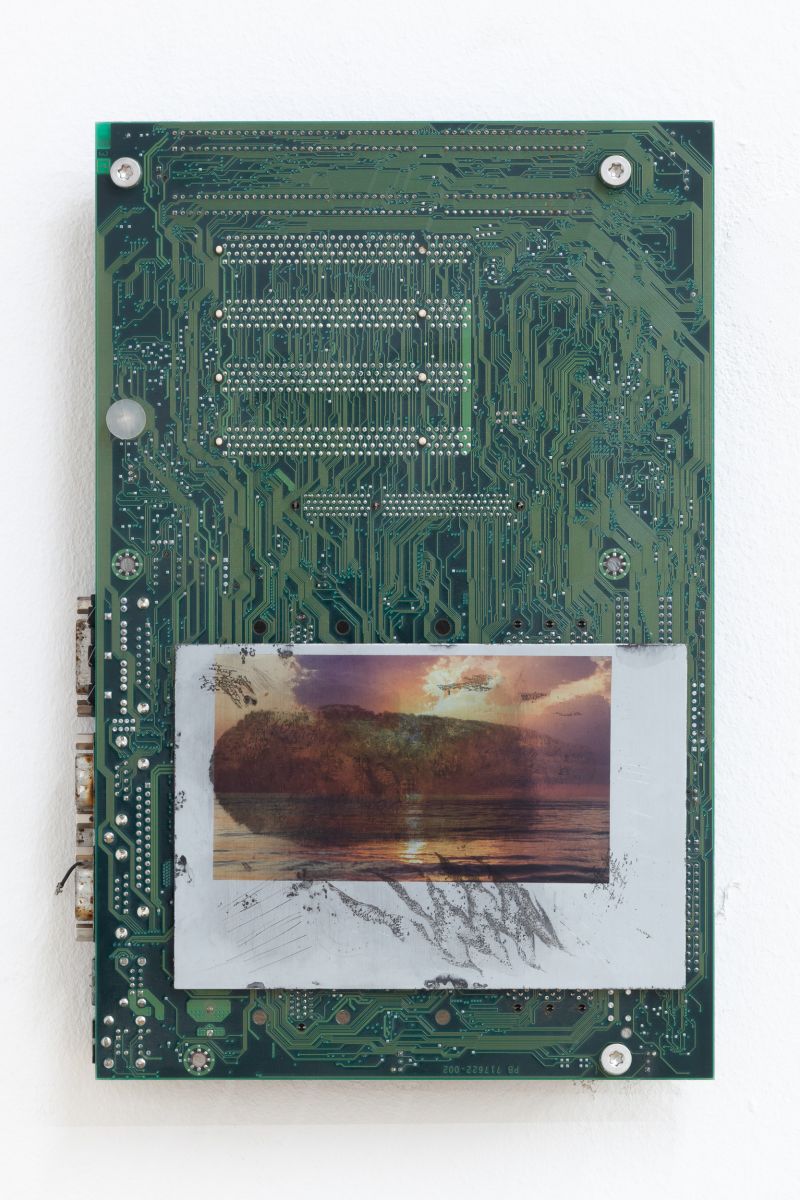

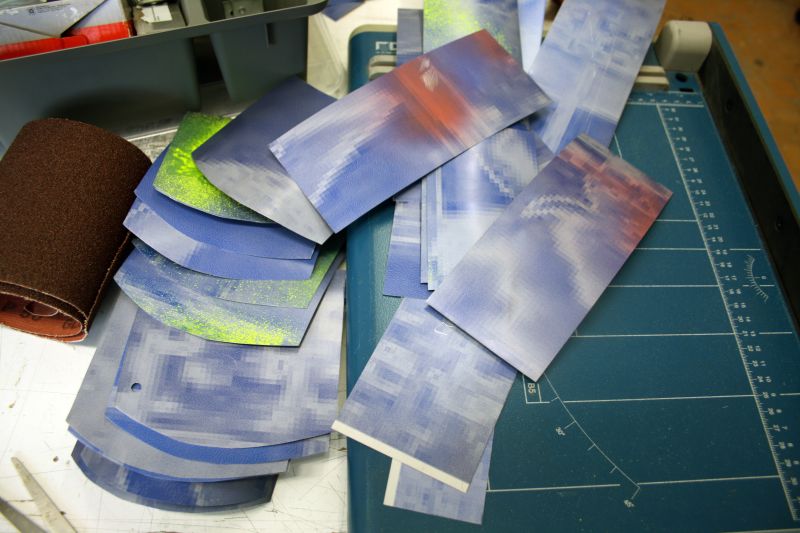

A-piece-of-metal-made-into-an-armor-made-into-an-etching-turned-into-an-electricity-conductor-powering-a-phone-showing-pixelated-images. During a chat, an art historian friend suddenly wondered aloud, “There is a connection between smartphone videos and printmaking plates, I just can’t articulate it yet. I only know that this connection is not dumb at all.” Maybe this connection is about generations of technology: the great-grandmother plate and its motherboard offspring. The relationship between mother and child is invoked throughout the history of technology, in the same way that the human brain is often compared to the latest technological achievement of the time—a hydraulic machine, a telegraph system, or a computer. While I’m still searching for a narrative myself, what I know is that, as technologies develop, the old ones don’t die completely and new ones don’t replace them fully. They all just kind of keep piling up in variable densities in weird places, as if a broken time machine has thrown up on our world. It is on this terrain that the invention of movable type encouraged people to think in straight lines and arrange their perceptions of the world within the limitations of a square page, and where, at this very moment, I am writing this text on a screen that imitates a sheet of paper.2

But once upon a time, a mother was an iron armor submerged in acid, since this text starts not with a woodblock, but with an etching.

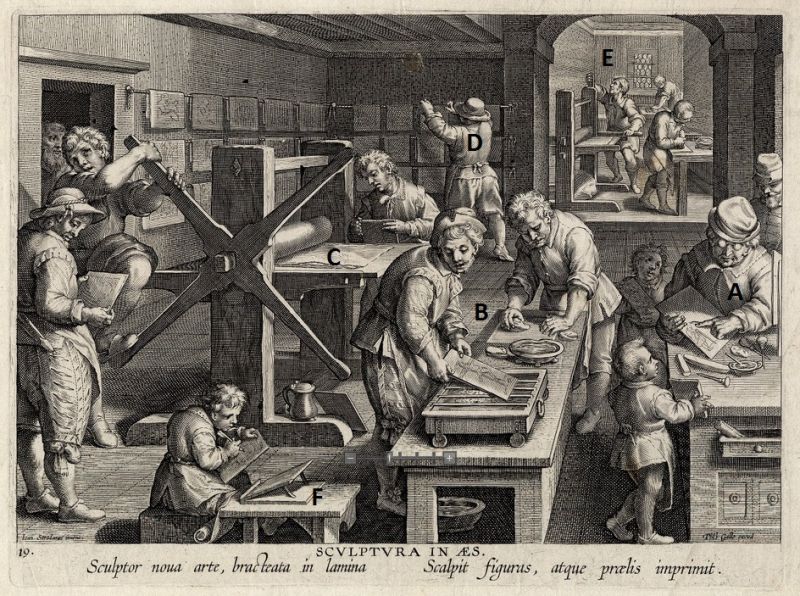

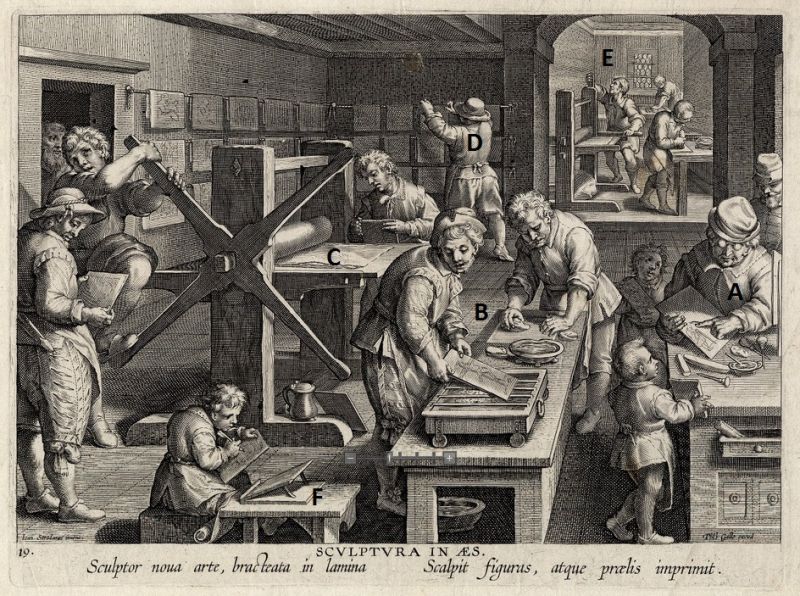

The earliest etching prints date back to the 15th century and are attributed to a German armorer named Daniel Hopfer. Without formal artistic training, he was both blessed and damned in his unboundedness to any particular aesthetic and genre. His imagery, spanning from decorative patterns to religious and secular scenes, has often been considered naive by art historians.

Smiths and artists who weren’t master woodcutters or engravers, but were able to hold a sharp pencil, could scratch the hard ground of the metal plate and dip it in acid, eroding the lines where the metal is exposed. While making a good quality engraving or print required considerable skill, etching matrices offered a more accessible technology for image making. Hopfer’s most significant contribution was that he used etching to reproduce and popularize prints not only by himself but also by others, producing a large repertoire of various types of prints of various subjects. According to Elizabeth Wyckoff, “In doing this, [Hopfer] was among the earliest of the entrepreneurs we would now call print publishers.”3

Etching quickly became a tool not only for imagination and self-expression but for the transmission and distribution of information. A medium for reproducing and reinterpreting images— reflecting the lifestyles of common people, mapping terrains, documenting the horrors of war, and circulating scientific illustrations and depictions of the monsters of local lore. Ocean Vuong writes, “I’m not a monster. I’m a mother”; Jeanette Winterson: “She was a monster but she was my monster.”4 And thus, the monster I refer to is the one that gives birth to the prints that shape the tongues, fears, and beliefs of vast groups of people. Books of marvels and beasts, now considered emblems of a dark age of ignorance and superstition, proliferated in the 15th and 16th centuries thanks to emergent printing technologies and the influential naturalists they helped create. In the illustrations of scientific explorations by Fortunio Liceti, Athanasius Kircher, or Ulisse Aldrovandi, the lines between fact and fiction were irrelevant as they were impossible to discern. Deformed newborns, Blemmyes, and two-headed animals comingled inside these printed pages. The rise of printing fostered a large and growing audience for literature about monsters, ushering the whole of Europe into what Lorraine Daston and Katharine Park refer to as the “age of wonder.”5 My own fascination with monsters came from attempts to dissect these menageries, to locate the origins of these beasts or what they represent. These inquiries were, in part, a means of rationalizing my own mother’s letters saying that queerness is monstrosity and that the fate of Sodom and Gomorrah awaits us.

In this age of wonder, another monster was born. A nation-beast, not imaginary, but imagined. In a theory built around the history of print capitalism, Benedict Anderson argues that print media gave birth to national identity around the world. After the proliferation of the Gutenberg-style printing press, bibles and newspapers were printed in local vernaculars, uniting people in the collective experience of a shared reality and identity and relegating those who did not share these experiences or identity to the pages of monster encyclopedias. “You’re not a monster,” finally answers Vuong to his mother. “What I really wanted to say was that a monster is not such a terrible thing to be. From the Latin root monstrum, a divine messenger of catastrophe, then adapted by the Old French to mean an animal of myriad origins: centaur, griffin, satyr. To be a monster is to be a hybrid signal, a lighthouse: both shelter and warning at once.”6 A mother is a monster, a shelter and a warning, a mother is a machinery of war.

The history of print is thus the history of a weapon to be destroyed. The other day, a friend told me how an edition of thousands of books she designed had to be reprinted because of a tiny mistake overlooked by the editors. The fresh and innocent, but “spoiled” edition had to be eradicated by the very printing house who birthed it, with the evidence captured on camera. A horrid day. I wanted to tell her that the question of destruction has always been there, since not just the beginning of print but the written word—the burning books, the ruined plates, the wrecked presses, all that. In the years of Soviet occupation, it was customary to damage print machines before throwing them away to prevent people from using them to print their own dissident literature. I learned this quite recently from Vaidotas Andziulis, whose father dug a secret underground printing house inside a hill in Kaunas in the ’80s with his own bare hands. The press was ironically named Hell’s Machine (Pragaro Mašina in Lithuanian) by Vytautas Andziulis, the founder of “ab.” Using his knowledge of printing technology, he constructed Hell’s Machine out of the discarded and wrecked parts of Soviet printmaking machines he gathered from scrap yards. You can imagine my disappointment when I learned that this mesmerizing underground anti-Soviet printing house published mostly patriotic and religious literature. One thinks that struggles for liberation are always progressive, but sometimes they bring us right back to where- or whatever we were running from.

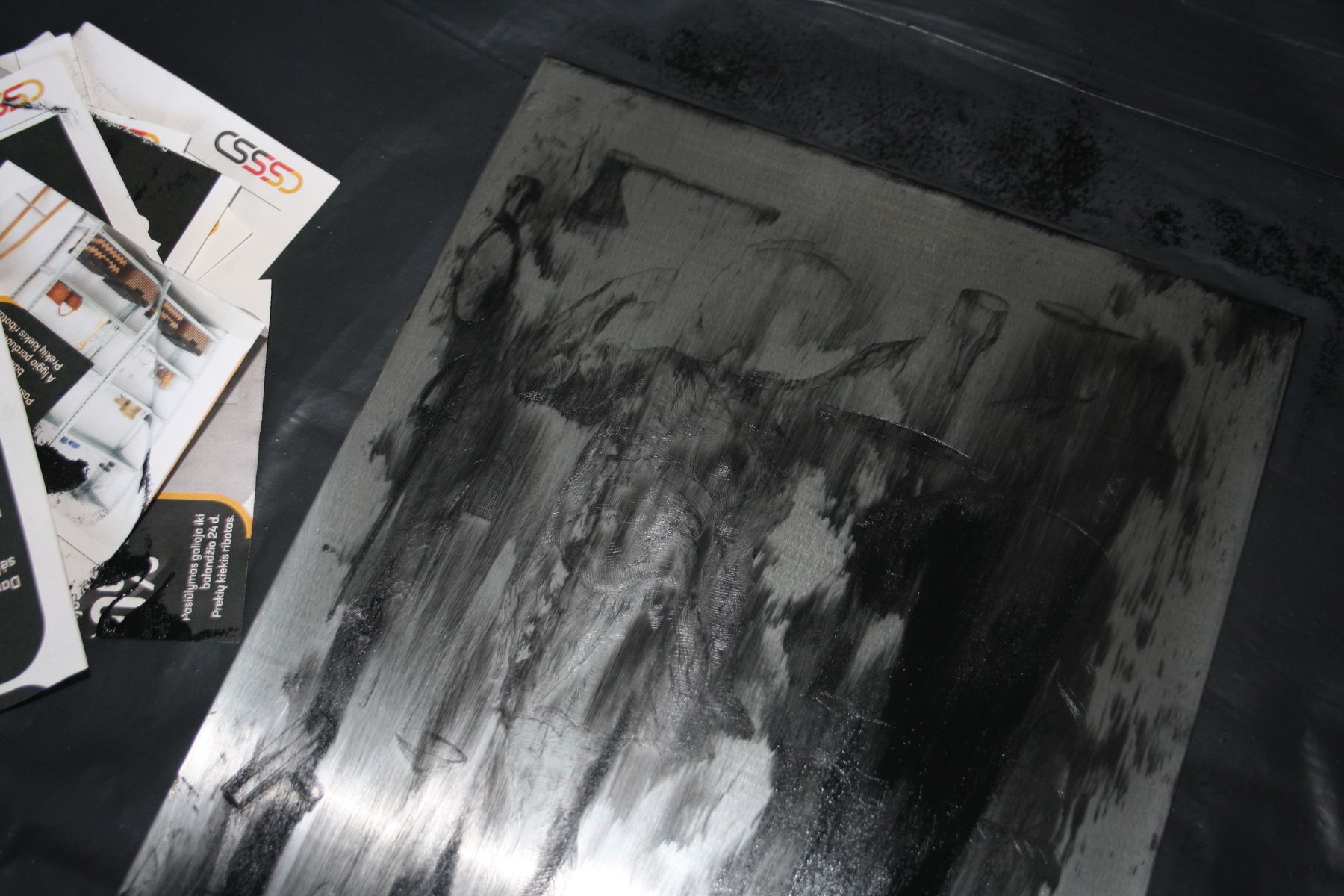

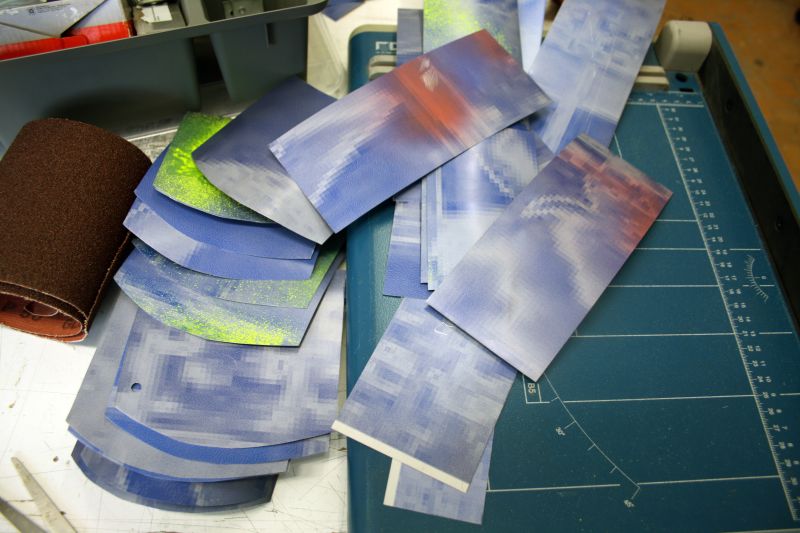

Perhaps, my fascination with unprinted matrices comes from dissatisfaction with their mirrored imprints. I remember feeling like I truly understood the tragedy of parenthood reading the lines of Guadalupe Natel’s Still Born. In the novel, Natel offers the metaphor of a cuckoo, a bird who leaves their eggs for other birds to hatch and raise as their own. The protagonist of the story posits a sinister theory that every mother is raising a cuckoo’s child, as if someone had deposited an egg in their nest and left: “We have children that we have, not the ones we imagine we’d have, or the ones we’d have liked, and they’re the ones we end up having to contend with.”7 It’s an inevitable tragedy. You always end up with something that is other than what you’ve expected. The child is not yours, because your true child is a phantom you dreamed, attempted to make, and failed to, utterly. I read Still Born while I worked endless hours on the etching matrix, which, when printed, produced something that was not quite what I wanted. The first prints are always a failure, one must apply ink and make a few test prints before it finally comes out well. There is a guild idiom for this process, “growing the image,” which refers to the ability of the matrix surface to “take in” ink through its repeated application in the process of test printing. Ultimately, enough ink builds up on the surface of the matrix to produce the perfect print. But even then, the perfect print is rarely good enough. A sigh of regret. A cuckoo’s child. It’s almost it, but somehow awkward, chiral.

But what of a matrix that has never and will never be printed? One of my mother’s griefs was my not wanting to become a mother. After I came out, it really dawned on her that there will be no kids. Not because I don’t want to, but because in her world, I just can’t. Maggie Nelson asks: “Is the presumed opposition of queerness and procreation (or, to put a finer edge on it, maternity) more a reactionary embrace of how things have shaken down for queers than the mark of some ontological truth? As more queers have kids, will the presumed opposition simply wither away? Will you miss it?”8 By exhibiting an etching plate and turning it into an untouchable artwork, the artist goes straight to the destruction of its primary function. Is it still a matrix? Or merely the ridged surface of a plaque?

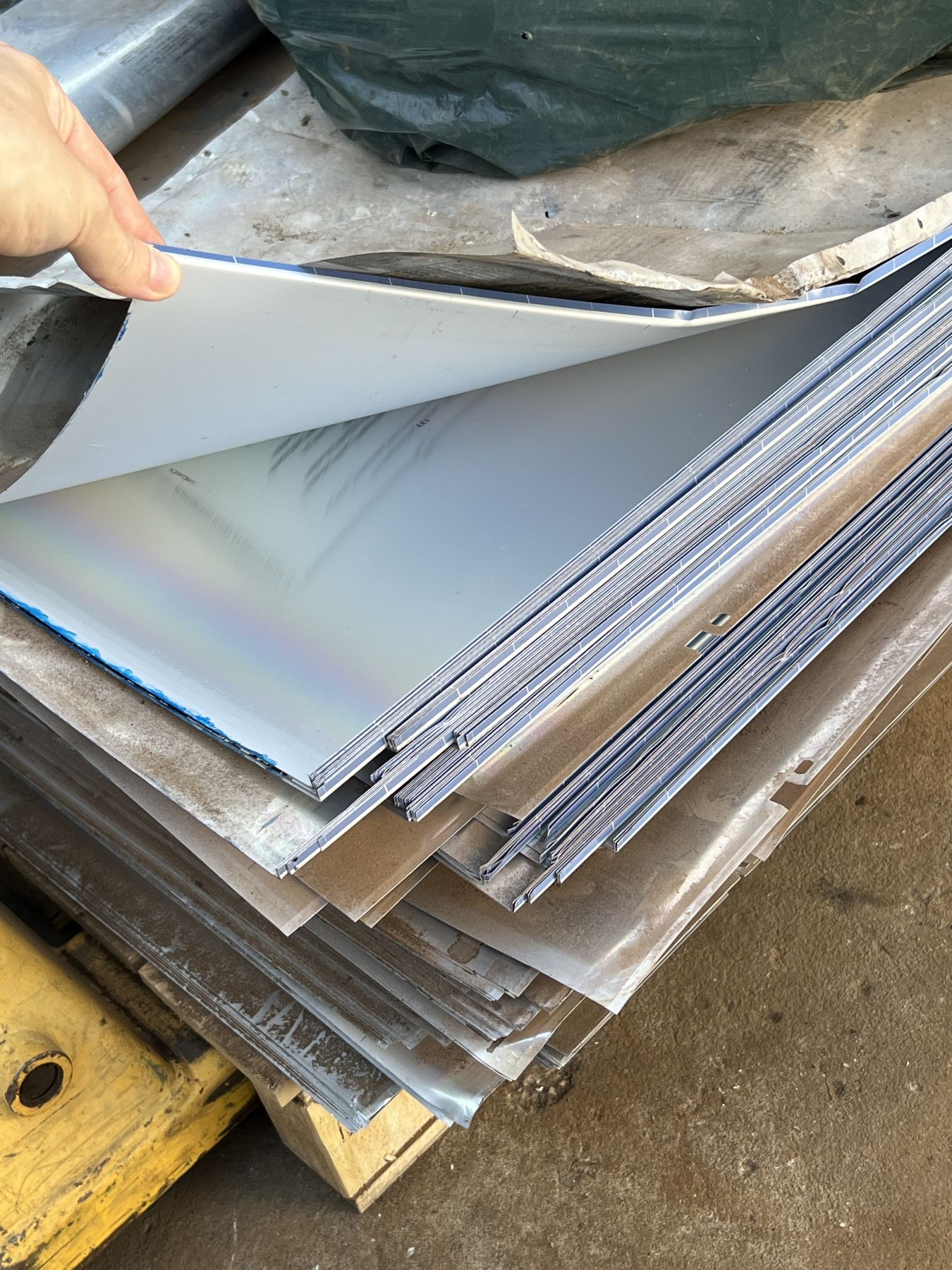

“...I wrote something about matricide, necessary for my own survival. I remember I was very honest because I told myself that honesty could be deliverance, that owning my rage could shrive the part of me that needed it.”9

And so, the history of the matrix is also the history of matricide. The first time I thought about this, I was reading Your Love Is Not Good by Johanna Hedva. In the story, the author’s recently deceased mother appears as a ghost ship, haunting the protagonist in her surroundings, in her dreams, in strangers, and, continuously, in her own face. Later, I was reminded of this vicious concept again by a friend who mentioned Julia Kristeva’s idea that becoming a speaking subject requires psychical matricide: violent separation from the maternal body. But in printmaking, the killing is the result of two conflicting realities: that the matrix is a precious origin, and that the matrix is production waste. There still exists an age-old custom in printmaking of destroying a plate, effectively closing the edition forever so that no one will ever be able to reproduce it. It’s a way to prevent access to the series and protect its authenticity. The other day, I saw tons of aluminum offset plates in recycling sites, discarded, ready to become something else. There’s no use for them anymore, and the flow of print production requires other matrices to be born. Where are their children? Does this relate to the digital file, endlessly copied and pasted? Poor images, so burnt and blurry they look deep fried. Do they have mothers? Will they meet their end?

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4]

[5]

[6]

REFERENCES

Ocean Vuong, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous (New York: Penguin Press, 2019), 52.

Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994), xi.

Elizabeth Wyckoff, “Daniel Hopfer, The Peasant Feast, c. 1533–36,” Learning Resources, Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, Sam Fox School of Design and Visual Arts, Washington University in St. Louis, accessed January 10, 2024, https://www.kemperartmuseum.wustl.edu/learn/learning-resources/hopfer-daniel-the-peasant-feast-c-153336/level/all.

Jeanette Winterson, Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal (New York: Grove Press 2012), 229.

Lorraine Daston and Katharine Park,Wonders and the Order of Nature, 1150–1750(New York: Zone Books, 2001), 361.

Ocean Vuong, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, 13.

Guadalupe Natel, Still Born (London: Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2022), 189.

Maggie Nelson,The Argonauts(Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2016), 13.

Johanna Hedva, Your Love is Not Good (Sheffield, UK: And Other Stories, 2023), 41.

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4]

[5]

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4]

[5]

[6]

REFERENCES

Ocean Vuong, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous (New York: Penguin Press, 2019), 52.

Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994), xi.

Elizabeth Wyckoff, “Daniel Hopfer, The Peasant Feast, c. 1533–36,” Learning Resources, Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, Sam Fox School of Design and Visual Arts, Washington University in St. Louis, accessed January 10, 2024, https://www.kemperartmuseum.wustl.edu/learn/learning-resources/hopfer-daniel-the-peasant-feast-c-153336/level/all.

Jeanette Winterson, Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal (New York: Grove Press 2012), 229.

Lorraine Daston and Katharine Park,Wonders and the Order of Nature, 1150–1750(New York: Zone Books, 2001), 361.

Ocean Vuong, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, 13.

Guadalupe Natel, Still Born (London: Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2022), 189.

Maggie Nelson,The Argonauts(Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2016), 13.

Johanna Hedva, Your Love is Not Good (Sheffield, UK: And Other Stories, 2023), 41.